When a child says “yes” out of politeness, fear, or a desire to be liked, they are more likely to be in a vulnerable position. Especially in a digital environment where requests from strangers, peer pressure and manipulation can be disguised as friendliness.

This is similar to the way a free phone number tracker works – essentially, it’s a useful tool that shows you a location to give you peace of mind. The important thing is not the tracking function, but the control over who sees you and when. It’s exactly the same with “no”: it becomes a power when a child decides who to trust, what to allow, and at what point.

So, today we are going to talk not about prohibitions, but about how to teach a child to say “no” calmly, confidently and without guilt. Step by step – from your own example to online hygiene and trusted communication. After all, “no” is not a refusal to communicate, it is an agreement to be safe.

Step 1: Your “No” Comes First

Before children can practice boundaries, they need to see them, and the best example here is you. If your child has never seen you say “no” – to invitations, extra work, social demands, or digital overload – they may interpret compliance as the only option.

So, firstly you need to normalize “no” through everyday language. Say it casually and calmly:

- “No, I don’t feel like going out today.”

- “No, thank you, I’m resting right now.”

- “No, this app wants too many permissions.”

And here is the key: explain your choice without defending it. Narrate it out loud: “I turned this off because I need quiet,” or “I didn’t reply to that message because it’s okay to respond later.” Children learn not just from the content of your decisions but from your tone, your confidence, and your lack of apology.

Thus, due to modeling refusal as reasonable, not rebellious, you will be able to lay the foundation for your child to do the same at school, in group chats, or when faced with uncomfortable questions or suggestions online.

Step 2: Explain that “No” Needs No Excuse

Most children (as well as adults) feel pressure to soften a refusal with justification. But in both digital and physical life, “no” is a complete sentence.

Teach your child that you and their decline doesn’t require an essay. Be it an invitation to a party or a request to send a selfie, they are allowed to simply say, “I don’t want to.” To empower them further, you may give them a go-to phrase, a verbal anchor: “I don’t want to, and that is okay” and then try to explain that this is not rudeness, only your calm personal boundaries.

By the way, in a recent UNICEF survey, over 60% of teens admitted they agreed to something online, e.g., joining a video call, sharing a photo, staying in a chat, just to avoid seeming mean. But kindness should not come at the cost of consent. Children must know that they are not responsible for managing others’ feelings at the expense of their own comfort.

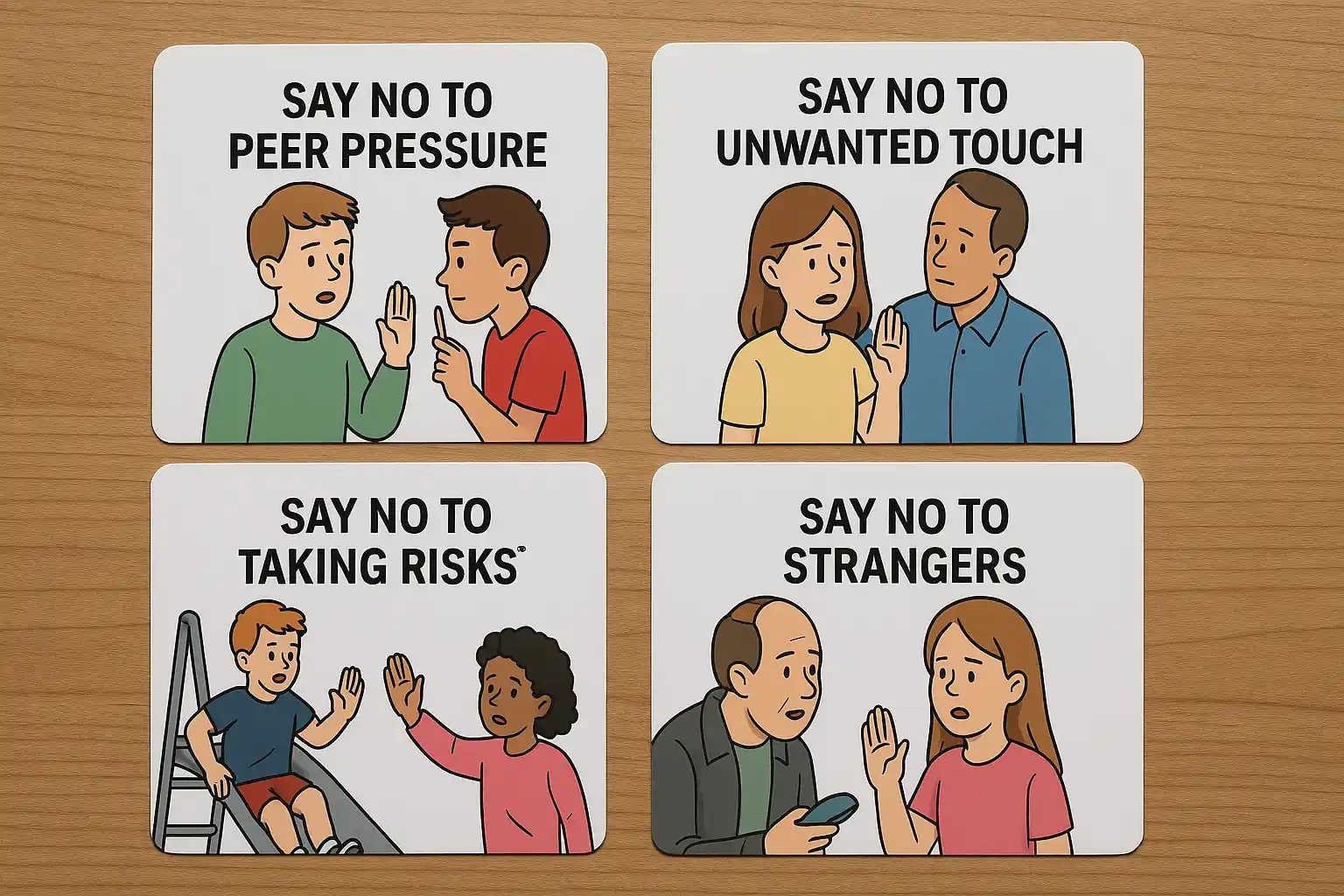

Step 3: Practice Scenarios and Role-Play

Just like we teach children to look both ways before crossing the street, we can also rehearse emotional and social safety. Practice doesn’t just build confidence, it rewires instinct. Saying “no” becomes easier when the child has already said it ten times in pretend conversations at home.

Here you can consider sitting together and role-playing various situations. Some can be lighthearted (“A classmate dares you to wear your pajamas to school”), while others should address serious scenarios. Some examples you may find in the table below.

| Situation | What to say | Coaching tip |

| A classmate dares your child to wear pajamas to school | “No thanks, not my thing.” | Start with lighthearted examples to ease into the exercise. Humor can reduce tension. |

| A stranger in an online game says, “Turn on your webcam” | “No. I don’t share camera with people I don’t know.” | Emphasize that “online strangers” are still strangers – and your “no” can be short and strong. |

| A peer messages, “Send me a funny pic, I won’t share it” | “No. I don’t send pictures like that.” | Remind your child that anyone asking for secrecy likely has the wrong intention. |

| A friend says, “Come with me, don’t tell anyone” | “If I can’t tell, then I won’t go.” | Use this to teach the link between secrecy and unsafe behavior. Secrets shouldn’t feel heavy. |

| A classmate says, “Don’t be boring, just say yes” | “I can be fun and still say no.” | Spot manipulation words like “boring” or “afraid” – they are common pressure tools. |

Lifehack: Create flashcards with tricky scenarios. Flip one, act it out, then discuss what felt easy or hard. Repeat it later with reversed roles, that enables your child to be the one enforcing boundaries. And remember that the key is not perfection, but muscle memory. With repetition, “no” becomes second nature, not something they try to find in a moment of doubt.

Step 4: Who Has the Right to Text You?

Boundaries also apply to the digital doorstep: messages, notifications, and pings. Children should understand that just because someone has their number or username doesn’t mean they have the right to their time or attention.

So, sit with your child and go through their contact list. Ask together:

- Who do you actually want to hear from?

- Who messages too often, too late, or makes you feel uncomfortable?

- When does a message cross from casual into pushy?

Now it will be wise to implement a strategy: digital “stop words.” This could be a short message like “I need a break now,” or an emoji code shared between you and your child that signals, “I want out of this chat.”

And here is where technology supports the lesson. Apps like Number Tracker, a well-known and reliable phone number tracker, let children share their location only with people they choose, and only when they feel safe doing so. It’s a quiet reminder: you are in control of your own presence.

Step 5: Spot Manipulation

Teaching a child to recognize manipulation is like giving them a flashlight in the dark – it won’t eliminate threats, but it helps them see what is happening. Manipulators often don’t shout, they whisper and don’t demand – they guilt, flatter, or challenge. Phrases like “I thought we were friends,” “Are you scared?” or “It’s just a joke” are classic traps designed to override a child’s instincts.

You don’t need to overwhelm them with warnings. Instead, talk together and list out phrases that feel off, not because they are loud, but because they are pushing. Then, brainstorm honest, self-assured responses to create together a kind of social armor, something they can pull out when needed.

According to the UK’s NSPCC, 73% of teens say they’ve agreed to something online under social pressure. That is nearly 3 out of 4 kids struggling to say “no” – not because they don’t want to, but because they weren’t sure how. So your main task is to make it clear: it’s okay to disappoint someone if it means protecting yourself.

“No” Isn’t a Wall but a Gate

Learning to say “no” doesn’t close doors, it opens the right ones. It teaches children that respect begins with themselves. In a world full of noise and pressure, one confident “no” can be the most powerful word they ever learn.